The Future of Digital Identity and Automated Compliance in Global Financial Services

How Verifiable Credentials and Blockchain Oracles are Forging a New Path for Automated Compliance.

Executive Summary

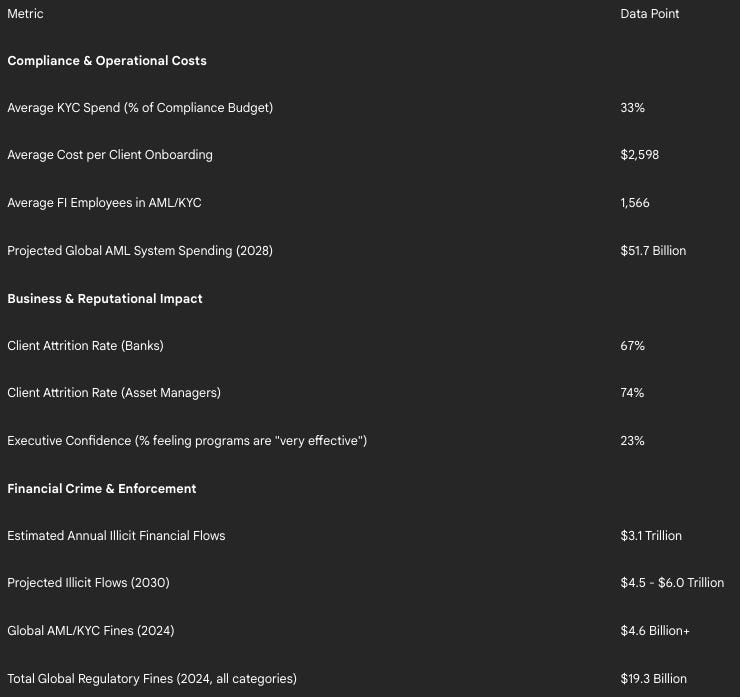

The global financial services industry is at a critical inflection point, burdened by an identity verification and compliance framework that is both economically unsustainable and strategically ineffective. Current Know-Your-Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) processes are manual, fragmented, and duplicative, consuming vast financial and human resources. Financial institutions spend, on average, one-third of their compliance budgets on KYC alone, yet illicit financial flows continue to surge into the trillions of dollars annually, and regulatory penalties for systemic failures have reached record-breaking levels. This paradigm is further strained by the inherent conflict between stringent data collection mandates and increasingly rigorous data privacy regulations like the GDPR, creating a "data dilemma" that perpetuates inefficiency and risk.

This report examines a proposed paradigm shift toward a decentralized, automated, and interoperable model for organizational identity, anchored by the verifiable Legal Entity Identifier (vLEI) and enabled by the Chainlink blockchain oracle network. The vLEI, a cryptographically secure digital counterpart to the globally recognized LEI, provides a regulator-friendly foundation for organizational identity. Chainlink furnishes the critical infrastructure for interoperability and privacy, allowing verified identity attributes to be used across multiple blockchains and legacy systems without exposing sensitive underlying data. Together, they offer a blueprint for a "verify-once, use-many" compliance model that promises to drastically reduce costs, accelerate client onboarding, and enhance security.

However, the path to adoption is fraught with significant challenges. The global regulatory landscape remains a complex and fragmented maze, with divergent approaches in the United States, the European Union, and the Asia-Pacific region. Technical hurdles, including the scalability of public blockchains, the security of smart contracts, and the immense difficulty of integrating with legacy financial systems, present formidable barriers. Furthermore, balancing the transparency of blockchain technology with the non-negotiable requirement for financial confidentiality demands sophisticated privacy-enhancing technologies that introduce their own complexities.

This analysis situates the vLEI and Chainlink solution within the broader digital identity ecosystem, comparing it to centralized, federated, and self-sovereign models, as well as burgeoning state-sponsored initiatives like the EU's Digital Identity Wallet. The report concludes that adoption will be driven not by a "big bang" replacement of existing systems, but by targeted implementation in high-friction, high-value use cases, particularly within the nascent tokenized asset economy. Ultimate success will depend on strategic collaboration between financial institutions, technology innovators, and forward-thinking regulators to build a new, programmable foundation of trust for the future of digital finance.

Part I: The Identity Compliance Crisis in Global Finance

Identity verification serves as the foundational defense for the global financial system, intended to safeguard against a litany of illicit activities including fraud, money laundering, and terrorist financing. Despite its critical importance, the prevailing frameworks for identity compliance are buckling under the weight of their own inefficiency, cost, and ineffectiveness. Financial institutions are trapped in a cycle of escalating expenditure and persistent failure, a crisis defined by three core dimensions: an unsustainable economic burden, an inability to meaningfully curb financial crime, and a paralyzing conflict with data privacy mandates.

1.1 The Crushing Weight of Compliance: Quantifying the Economic Burden

The economic resources dedicated to current KYC and AML protocols are staggering, reflecting a system characterized by manual, fragmented, and endlessly repeated processes. Each financial institution operates in a compliance silo, forced to re-verify the same customer information that has already been verified by its peers. This duplication is driven by a combination of stringent data protection requirements, jurisdictional policy differences, and a lack of shared technical standards.

The direct costs are immense. A 2024 survey revealed that financial institutions in major hubs like the United Kingdom, the United States, and Singapore allocate approximately 33% of their entire compliance budgets to KYC processes alone. This expenditure translates into a significant operational load. On average, a global financial institution involves 1,566 full-time employees in its AML/KYC processes, culminating in an average cost of $2,598 for each new client onboarding. The overall global spending on AML systems is projected to climb to $51.7 billion by 2028, with the market for specific AML software and services expected to reach $2.9 billion in 2025.

These high costs are not just a line item on a budget; they have profound business consequences. The slow and cumbersome nature of these manual onboarding processes creates significant friction for customers, leading to substantial client attrition. Fenergo estimates that these inefficiencies have caused 67% of banks and 74% of asset managers to lose clients who are unwilling to endure the lengthy and repetitive verification procedures.

The primary driver behind these escalating costs is human labor. In the past year, 72% of financial institutions reported higher labor costs for their compliance staff, while 70% faced rising expenses for compliance training. For large companies, the cost of simply maintaining compliance can reach as high as $10,000 per employee, an expense that has surged by over 60% since the pre-2008 financial crisis era. This evidence points to a fundamental paradox within the industry: firms are dedicating ever-increasing financial and human resources to compliance, yet the outcomes are not improving proportionally. The problem is not one of insufficient spending but of a deeply flawed and inefficient operational model. This points to a strategic misallocation of resources on a massive scale. The thousands of employees at each institution engaged in these manual, repetitive tasks represent a significant opportunity cost. This talent could be redirected toward innovation, strategic growth, and improved customer service if the underlying compliance processes were automated and streamlined. The crisis is therefore not merely financial; it is a profound drain on the industry's human capital.

1.2 A Losing Battle: The Unrelenting Scale of Financial Crime and Regulatory Penalties

Despite the billions spent on compliance, the financial system remains remarkably vulnerable to sophisticated financial crime. The scale of the problem is vast and growing. According to a Nasdaq report, an estimated $3.1 trillion in illicit funds flowed through the global financial system in 2023. This figure includes hundreds of billions from activities like drug trafficking ($782.9 billion) and human trafficking ($346.7 billion). Fraud losses from scams and bank fraud schemes added another $485.6 billion to the global toll. Looking forward, the outlook is even more concerning, with some estimates projecting that illicit financial flows could surge to between $4.5 trillion and $6 trillion by 2030.

This operational failure to stem the tide of illicit finance is met with increasingly severe regulatory consequences. In 2024 alone, financial institutions faced $4.6 billion in fines for failing to meet AML and KYC obligations. Some analyses place the figure for total global regulatory fines even higher, at a record-breaking $19.3 billion in 2024, a sum heavily influenced by monumental penalties against both crypto firms and traditional banks.

Recent enforcement actions reveal a significant shift in regulatory posture. Authorities are no longer just penalizing isolated breaches but are targeting deep-seated, systemic failures in risk management frameworks. The case against TD Bank, which agreed to pay approximately $3.1 billion in fines in 2024 for severe Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) and AML violations, is a landmark example. The investigation revealed that the bank's systemic failures enabled money laundering networks to move over $670 million. Critically, prosecutors pursued charges on the basis that the bank's violations were willful, partly driven by a desire to avoid the high costs of robust compliance. This sets a powerful precedent, signaling that regulators are now willing to "second-guess compliance resourcing decisions," making underinvestment in compliance a direct and severe legal liability.

This heightened scrutiny is not confined to traditional banking. The regulatory perimeter is visibly expanding. Major crypto exchanges like Binance, which faced a $4.3 billion penalty, and KuCoin, which paid nearly $300 million, have been targeted for operating as unlicensed money transmitters and failing to prevent illicit transactions. Furthermore, AML obligations are being extended beyond finance to other "gatekeeper" industries, including legal services, accountancy, and gaming, creating a much broader market for effective identity solutions. This expansion underscores the need for any future identity framework to be adaptable to a wide range of business models.

The result is a profound confidence gap within the industry. A 2025 Kroll survey found that while 71% of global executives expect financial crime risk to increase, only 23% believe their own compliance programs are "very effective" at mitigating these threats. The rise of AI-powered cybercrime is a top concern, with 75% of anti-financial crime professionals rating generative AI for malicious purposes as a high or very high risk. The current approach is clearly failing, leaving institutions exposed to massive financial penalties, lasting reputational damage, and a persistent loss of client trust.

Table 1: The Economic Impact of Current KYC/AML Regimes

1.3 The Data Privacy Paradox: Navigating GDPR and PII Obligations

Compounding the challenges of cost and ineffectiveness is a fundamental conflict between compliance mandates and data protection regulations. On one hand, FIs are required by AML/KYC rules to conduct extensive due diligence, which involves collecting and storing vast amounts of sensitive Personally Identifiable Information (PII). On the other hand, landmark data protection laws, most notably the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), impose substantial and complex obligations on any organization that handles such data.

These regulations introduce stringent requirements, including ensuring data sovereignty (controlling where data is physically stored), preventing unauthorized data transfers outside specific jurisdictions like the EU, and upholding individual rights such as the right to data access, correction, and erasure (the "right to be forgotten"). This creates a "Data Dilemma": the very act of complying with one set of regulations (AML/KYC) increases the risk and liability associated with another (data privacy).

This paradox is a primary structural driver of the inefficiency plaguing the financial industry. It is the key reason why a more efficient, shared-utility model for KYC has not emerged. Financial institutions are intensely "wary of managing customer data internally" due to the associated regulatory burdens and are even more hesitant to share verified identity information with other firms. The act of sharing data itself creates a web of complex legal and data-protection liabilities under regimes like GDPR, forcing each institution to build and maintain its own isolated data silo. This institutional fragmentation and duplication of effort is a direct consequence of managing data privacy risk.

This inherent tension, however, is also a powerful forcing function for technological innovation. The conflict between the need for robust verification and the strict rules governing data privacy creates a compelling business case for the adoption of Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs). Solutions that can verify a required attribute—for example, that a customer is not a sanctioned individual or is over a certain age—without exposing or transferring the underlying PII are no longer a niche academic concept. Cryptographic proofs, zero-knowledge proofs, and other PETs that enable verification on a "need-to-know" basis are becoming a strategic necessity to resolve this fundamental operational and legal conflict at the heart of modern finance.

Part II: A New Paradigm – Decentralized Identity with vLEI and Chainlink

In response to the systemic failures of the current identity verification model, a new paradigm is emerging, built on the principles of decentralization, cryptographic verifiability, and interoperability. This approach seeks to move away from the fragmented, siloed model where verification is endlessly duplicated toward a more efficient framework where identity can be securely verified once and reused across multiple entities. At the core of this proposed solution for organizational identity are two synergistic technologies: the verifiable Legal Entity Identifier (vLEI) as the standard for trusted identity, and the Chainlink network as the engine for interoperability and privacy-preserving data connectivity.

2.1 Foundations of a Verifiable Future: The Verifiable Legal Entity Identifier (vLEI)

The verifiable Legal Entity Identifier (vLEI) is not a new identity system created from scratch, but a digital evolution of an existing, globally recognized standard. It builds upon the ISO 17442 Legal Entity Identifier (LEI), a 20-character code that provides a unique identifier for legal entities involved in financial transactions. The LEI system was established in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis to increase transparency in financial markets and is already mandated by over 200 regulators worldwide.

The vLEI transforms this static, database-referenced LEI into a dynamic, cryptographically secure digital credential. It functions as a digital passport for an organization, enabling automated, real-time verification of its identity without the need for manual checks or human intervention. This is achieved through a robust technical architecture built on open standards. The ecosystem primarily uses the

Key Event Receipt Infrastructure (KERI) for secure identifier and cryptographic key management, and Authentic Chained Data Containers (ACDC) as the standardized format for the credentials themselves. These technologies ensure that a vLEI credential is both authentic and tamper-proof.

The trust architecture of the vLEI ecosystem is clear and hierarchical. The Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation (GLEIF), a supra-national non-profit organization established by the G20 and the Financial Stability Board, acts as the ultimate "Root of Trust". GLEIF issues cryptographic credentials to a network of

Qualified vLEI Issuers (QVIs). These QVIs are then authorized to perform the necessary due diligence and issue vLEI credentials to legal entities, which can be stored in a digital wallet.

A critical innovation of the vLEI system is its ability to go beyond simple entity identification to manage authorization and delegation. Through the issuance of role-based credentials, an organization can prove that a specific individual is authorized to act on its behalf in a particular capacity. This is facilitated by two key types of credentials:

Official Organizational Role (OOR) Credentials: These link an individual to a formal, publicly verifiable role within an organization (e.g., CEO, Board Chair), based on standards like ISO 5009.

Engagement Context Role (ECR) Credentials: These offer more flexibility, allowing an organization to define and issue credentials for custom roles based on specific business engagements (e.g., "Authorized Signatory for Project X," "Verified Supplier").

The most significant attribute of the vLEI is its function as a "trust bridge." Because it is an evolution of the pre-existing, regulator-endorsed LEI system, it provides a familiar and trusted anchor point for bringing identity into the on-chain world. This dramatically lowers the barrier to regulatory acceptance compared to purely crypto-native or anonymous identity systems. It offers a path for traditional finance (TradFi) to engage with the digital asset economy using an identity standard that is already understood and integrated into existing regulatory frameworks.

Furthermore, the OOR and ECR credentials transform identity from a static, one-time check into a dynamic, programmable component of automated workflows. This creates a foundation for programmable corporate identity and authority. This capability is essential for automating complex B2B financial processes like trade finance, corporate treasury management, and supply chain logistics, where verifying not just who the counterparty is, but also the specific authority of the individual executing the transaction, is paramount.

2.2 The Interoperability Engine: Chainlink's Role in Connecting On-Chain Identity

For a digital identity credential like the vLEI to be truly useful in a diverse financial ecosystem, it must be portable and usable across different platforms. This is the critical role fulfilled by Chainlink, a decentralized oracle network that acts as a secure middleware layer, connecting on-chain smart contracts with off-chain data, APIs, and legacy financial systems.

Chainlink's core function is to solve the "oracle problem": blockchains, by design, cannot access external data. Chainlink addresses this by using a decentralized network of independent, economically incentivized node operators to fetch, validate, and deliver external data to smart contracts. This decentralized approach mitigates the risk of a single point of failure or data manipulation that would exist with a centralized oracle.

The financial world is not, and will not be, built on a single blockchain. It is an interconnected web of public blockchains (like Ethereum), private or permissioned blockchains used by consortia of banks, and traditional legacy systems. Recognizing this reality, Chainlink has developed the Cross-Chain Interoperability Protocol (CCIP). CCIP serves as a secure and standardized messaging and value transfer protocol that allows smart contracts on one chain to communicate with and send assets to another. This positions Chainlink as the essential "translation layer" or interoperability engine that can make a digital identity like the vLEI portable across this fragmented landscape.

For institutional adoption, privacy is non-negotiable. Chainlink is actively developing a suite of institutional-grade, privacy-preserving technologies to meet these needs. This includes the Blockchain Privacy Manager, which allows institutions to integrate their private chains with the public Chainlink network without exposing sensitive data, and DECO, a protocol that uses Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) to enable privacy-preserving data verification. These tools are designed to allow institutions to transact confidentially, even when using public blockchain infrastructure.

Chainlink's viability is further bolstered by its vast and growing ecosystem, which includes over 2,300 projects and deep partnerships with key players in both the crypto and traditional finance worlds. Collaborations with financial infrastructure giants like Swift and Euroclear, payment networks like Mastercard, and regulatory bodies such as the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) demonstrate a clear strategy of bridging the gap between the existing financial system and the emerging on-chain economy.

This combination of services—secure data feeds, cross-chain interoperability, and privacy tools—points toward the potential "platformization" of compliance. Rather than each financial institution building its own bespoke compliance technology stack, they could leverage Chainlink's decentralized network as a service. Through this platform, they could access verified identity data (like a vLEI), move assets securely via CCIP, and execute compliance logic through smart contracts, all while preserving the confidentiality required for institutional finance. This could fundamentally transform compliance from a massive internal cost center into a more efficient, on-demand, network-based utility.

2.3 Synergy in Action: A Blueprint for Automated, Privacy-Preserving Compliance

The combination of GLEIF's vLEI and Chainlink's infrastructure creates a powerful, synergistic solution for the challenges facing global finance. The model provides a clear blueprint for how automated, privacy-preserving compliance can function in a digital asset ecosystem.

The process works as follows:

An organization obtains a vLEI from a Qualified vLEI Issuer, establishing a cryptographically secure and globally recognized proof of its legal identity.

When this organization needs to interact with a financial service (e.g., open an account, trade a tokenized asset), a smart contract can request verification of its identity.

A Chainlink oracle can securely query the vLEI credential and use its verified attributes to satisfy compliance checks within the smart contract. Crucially, this can be done without exposing the underlying sensitive data on the public blockchain.

This enables organizations to share relevant identity attributes on a "need-to-know" basis. For example, a smart contract could verify that an entity is not on a sanctions list and is domiciled in an approved jurisdiction, receiving a simple, cryptographically signed "yes/no" answer from the oracle network without the entity's full corporate details ever being broadcast on-chain.

This synergistic model directly resolves the "Data Privacy Paradox" identified in Part I. The vLEI serves as the trusted identity anchor, while Chainlink's privacy-preserving oracles act as the secure intermediary that allows for verification without necessitating the transfer or exposure of raw PII. This fundamentally shifts the compliance paradigm from a repetitive, siloed, in-house verification process to a "verify-once, use-many" framework. This change promises to dramatically reduce redundant work, minimize data exposure, and significantly accelerate processes like client onboarding and transaction execution.

This framework is particularly vital for the future of tokenized assets. As real-world assets like bonds, commodities, and private equity are represented as tokens on blockchains, maintaining a single, authoritative source of truth—a "golden record"—for associated data becomes critical. This record must track ownership, liens, and compliance status as the asset moves across different chains. The vLEI can serve as the unique, verifiable identifier for the legal entity that owns the asset, while Chainlink's CCIP and data feeds can ensure that this golden record remains synchronized and consistent across the entire multi-chain ecosystem. This provides the foundational infrastructure needed for a trusted and truly interoperable tokenized asset economy.

Part III: Critical Analysis – Challenges and Headwinds for Blockchain-Based Identity

While the vision of a decentralized, automated compliance framework is compelling, the path to its realization is fraught with significant and complex challenges. A nuanced analysis requires a clear-eyed assessment of the formidable headwinds that the vLEI/Chainlink model—and indeed any blockchain-based identity system—must navigate. These challenges span the regulatory, technical, and privacy domains and will ultimately determine the pace and scope of adoption.

3.1 The Regulatory Maze: Navigating Global Uncertainty and Jurisdictional Divergence

The single greatest barrier to the widespread adoption of blockchain-based identity is the lack of a clear, consistent, and globally harmonized regulatory framework. Many governments and regulators are still in the early stages of understanding the technology, resulting in a patchwork of rules, guidance, and enforcement actions that creates profound uncertainty for market participants. This landscape is characterized by starkly different approaches in key jurisdictions.

United States: The U.S. regulatory environment is notably fragmented and often driven by enforcement rather than proactive rulemaking. Agencies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) hold differing views on which digital assets constitute securities, leading to a "regulation by enforcement" climate that stifles innovation. While the SEC's Crypto Task Force aims to provide clarity, its actions are often perceived as inconsistent. At the same time, a complex web of state-level laws, such as California's Digital Financial Assets Law (DFAL) and Arizona's rules for cryptocurrency kiosks, adds further layers of compliance complexity. On the identity front, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) is beginning to issue guidance on the use of digital IDs for Customer Identification Program (CIP) requirements, but recent rollbacks and confusion surrounding the Corporate Transparency Act's beneficial ownership rules have created new burdens for banks, forcing them to rely more heavily on their own verification processes.

European Union: In contrast, the EU has adopted a more proactive and comprehensive, framework-driven approach. The landmark eIDAS 2.0 regulation establishes a legal foundation for a pan-European digital identity system, mandating that all member states offer citizens a free European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDI Wallet) by 2026. This wallet is designed to be a secure, user-controlled platform for both national eIDs and other verifiable credentials, and its acceptance will be mandatory for regulated industries requiring Strong Customer Authentication (SCA). However, even within this structured approach, tensions exist. Recent draft guidelines from the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) on storing personal data on blockchains could create new conflicts with GDPR's principles, highlighting the ongoing difficulty of reconciling immutable ledger technology with data protection law.

Asia-Pacific (APAC): Leading financial hubs in APAC, such as Singapore and Hong Kong, are pursuing a strategy of creating clear but stringent licensing regimes for digital asset service providers. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has expanded its Payment Services Act and established a demanding framework for Digital Token Service Providers (DTSPs), with a heavy emphasis on AML/CFT, consumer protection, and technology risk management. Similarly, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) is implementing a licensing regime for stablecoin issuers and has provided detailed guidance on the secure custody of digital assets, setting a high bar for market entry.

Global Standards: At a global level, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) sets the overarching principles for AML/CFT. Its standards, particularly Recommendation 15 (which applies AML rules to Virtual Asset Service Providers, or VASPs) and Recommendation 16 (the "Travel Rule," requiring the exchange of originator and beneficiary information), are the global benchmark. The FATF has also issued specific guidance on the use of digital ID for Customer Due Diligence (CDD), emphasizing the importance of a risk-based approach and assessing the "assurance level" of any given identity system to ensure it is sufficiently reliable and independent.

This complex global environment creates a "Compliance Trilemma" for any global identity solution. It must be designed to simultaneously satisfy the often-conflicting, specific rules of multiple jurisdictions; adhere to the high-level principles of global bodies like the FATF; and function within the technical and operational constraints of a decentralized network. The immense difficulty of navigating this maze inadvertently creates a powerful competitive moat. Only well-capitalized and strategically sophisticated players—such as the G20-backed GLEIF and the enterprise-focused Chainlink—possess the resources to effectively engage with this complexity. This could, paradoxically, lead to a future where the "decentralized" identity ecosystem is dominated by a few large, quasi-institutional players who are capable of managing this regulatory burden.

Table 2: Global Regulatory Snapshot for Digital Assets and Identity

3.2 Technical Hurdles: The Trilemma of Scalability, Security, and Legacy Integration

Beyond the regulatory maze, a host of formidable technical challenges stand in the way of adoption. These hurdles relate to the inherent limitations of the underlying technology and the immense difficulty of integrating it into the existing financial infrastructure.

Scalability: Public blockchains are famously constrained by the "blockchain trilemma," a concept suggesting that a network can optimize for only two of three key properties: decentralization, security, and scalability. Most foundational blockchains, like Bitcoin and Ethereum, have prioritized decentralization and security, resulting in significant scalability limitations. Bitcoin can process around 7 transactions per second (TPS), while Ethereum handles approximately 30 TPS. These speeds are orders of magnitude slower than centralized payment systems like Visa, which can process thousands of TPS, and are insufficient for the demands of global finance. This low throughput leads to network congestion during periods of high demand, causing transaction fees to spike and confirmation times to lengthen, which hinders mainstream adoption and makes many use cases, such as microtransactions, economically unviable. While Layer-2 scaling solutions and newer, faster blockchains aim to address this, the performance of any application built on a blockchain is ultimately constrained by the capacity of its foundational layer.

Security: The core logic of the proposed solution resides in smart contracts, which are self-executing pieces of code deployed on a blockchain. While the blockchain itself may be immutable, the code within the smart contracts can contain vulnerabilities that can be exploited with devastating consequences. The history of decentralized finance is littered with examples of hacks that have resulted in billions of dollars in losses due to common smart contract flaws. These include:

Reentrancy Attacks: A malicious contract repeatedly calls a function in a target contract before the first call is complete, allowing it to drain funds.

Oracle Manipulation: An attacker manipulates the external data fed into a smart contract by an oracle to trigger unintended outcomes, such as taking out an undercollateralized loan.

Logic Errors and Integer Overflows: Simple coding mistakes or mathematical errors can lead to flawed calculations that allow attackers to claim excessive rewards or steal assets.

The security of the entire vLEI/Chainlink system depends on the flawless design and rigorous auditing of these smart contracts.

Legacy Integration: Perhaps the most daunting technical challenge is integrating a decentralized, modern technology like blockchain with the decades-old legacy systems that form the backbone of the global financial industry. These systems are often monolithic in architecture, written in older programming languages like COBOL, and rely on rigid, centralized databases. Integrating them with a blockchain network is fraught with difficulty, including technical incompatibility, complex data migration challenges, and significant security risks at the integration points. This process is not only technically complex but also extremely costly and faces significant organizational and cultural resistance to change from employees accustomed to established workflows.

These technical hurdles mean that the performance of the vLEI/Chainlink solution is not determined by its own design alone, but is dependent on the weakest link in the chain—be it the speed of the underlying blockchain or the fragility of the legacy system it connects to. Furthermore, the immense cost and risk associated with overhauling mission-critical legacy infrastructure may prove to be a greater barrier to adoption than the potential savings in compliance. This suggests that adoption is more likely to occur in "greenfield" projects, such as new platforms for tokenized assets, rather than through a wholesale "rip and replace" of existing KYC systems at large, incumbent institutions.

3.3 The Privacy Tightrope: Balancing On-Chain Transparency with Off-Chain Confidentiality

A fundamental paradox lies at the heart of using public blockchains for identity: their greatest strength, transparency, is also their greatest liability from a privacy perspective. The public and immutable nature of a blockchain ledger means that every transaction is recorded permanently and is visible to anyone on the network. While wallet addresses are pseudonymous, if an address is ever linked to a real-world identity, that individual's entire history of transactions—every payment, every trade, every interaction—can be traced and analyzed.

The 2022 bankruptcy of the crypto lending platform Celsius provided a stark, real-world demonstration of this risk. As part of the court proceedings, the names and transaction histories of nearly half a million depositors were made public, allowing anyone to link their real-world identities to their on-chain activities. For financial institutions, which operate under strict confidentiality requirements, broadcasting transaction details on a public ledger is a non-starter.

This transparency also creates a direct conflict with data protection regulations like GDPR, which includes principles such as data minimization and the "right to be forgotten". The immutable, "append-only" nature of blockchain makes it technically difficult, if not impossible, to honor a request for data erasure, placing on-chain data storage in direct opposition to legal requirements. Consequently, storing raw PII on a public blockchain is not a viable option for any regulated use case.

The vLEI/Chainlink model is designed to navigate this privacy tightrope by fundamentally flipping the traditional identity data model. Instead of centralizing data for verification, this model keeps sensitive data off-chain (e.g., with the user in a digital wallet) and uses the blockchain to verify cryptographic proofs about that data. Technologies like

Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) are central to this approach. A ZKP allows a user (the "prover") to prove to a verifier that a statement is true (e.g., "I am an accredited investor" or "I am not on a sanctions list") without revealing any of the underlying information used to establish that fact. The smart contract doesn't see the user's financial statements or personal details; it only receives a valid, cryptographically signed proof that the required conditions are met.

While this model elegantly solves the problem of storing PII on-chain, it introduces a new and highly complex attack surface at the intersection of the on-chain and off-chain worlds. The security of the entire system now hinges on the integrity of multiple components:

The oracles (e.g., Chainlink nodes) that may be needed to fetch external data to validate a proof.

The user's digital wallet, where the private keys and verifiable credentials are stored. A compromise of the wallet could lead to identity theft.

The mathematical soundness and implementation of the cryptographic proofs themselves. A flaw in a ZKP protocol could allow a malicious actor to generate false proofs.

Therefore, even if the blockchain itself remains secure, a vulnerability in any of these interconnected components could undermine the integrity of the entire identity system. Successfully balancing transparency and confidentiality requires not only innovative cryptography but also a holistic security posture that spans on-chain and off-chain environments.

Part IV: The Competitive and Strategic Landscape

The vLEI and Chainlink model does not exist in a vacuum. It enters a dynamic and evolving digital identity landscape populated by competing philosophies, technologies, and powerful strategic actors. To understand its potential trajectory, it is essential to analyze its position relative to other identity frameworks, the impact of major government-led initiatives, and the role of other emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and biometrics.

4.1 Mapping the Digital Identity Ecosystem: A Comparative Analysis

Digital identity is not a monolithic concept; it is a spectrum of models, each with different trade-offs regarding control, security, and user experience. The primary models can be broadly categorized as follows:

Centralized Model: This is the traditional approach where a single entity—a corporation (e.g., a bank), a government agency, or a tech company—creates, manages, and is the sole arbiter of an individual's digital identity. Its primary benefits are simplified management, clear lines of accountability, and ease of integration into existing corporate structures. However, its weaknesses are profound: it creates massive, centralized databases of PII that are prime targets for data breaches, it offers users little to no control over their own data, and it results in a fragmented system where users must maintain dozens of separate identities.

Federated Identity Model (FIM): This model, familiar to anyone who has used "Log in with Google" or "Log in with Facebook," establishes a trust relationship between multiple, separate organizations. An

Identity Provider (IdP), like Google, authenticates the user and then passes a secure assertion of that identity to a Service Provider (SP), like a third-party application. Built on open standards like SAML and OpenID Connect (OIDC), FIM dramatically improves user experience by enabling Single Sign-On (SSO) across different domains. While more user-friendly, it still relies on a few large, centralized IdPs, concentrating immense power and data in their hands and creating significant privacy and competition concerns.

Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) Model: This is the most philosophically decentralized approach. SSI aims to give individuals ultimate control and ownership over their own digital identities. In an SSI model, the user employs a

digital wallet on their personal device to store verifiable credentials (VCs)—digital versions of passports, diplomas, or licenses—issued by trusted entities. The user then has sole discretion over when, how, and with whom to share these credentials, often using selective disclosure to reveal only the necessary information. This model enhances privacy and portability but faces significant challenges in user adoption, digital literacy, and establishing universally accepted governance frameworks.

The vLEI/Chainlink model occupies a unique, hybrid position on this spectrum. While it leverages decentralized technologies like blockchain and oracles, its architecture is not purely self-sovereign. The ultimate "trust anchor" of the system is not the individual user but GLEIF, a single, globally-governed, G20-backed foundation. This makes the vLEI model more centralized than pure SSI but more decentralized than the federated model, which relies on a handful of tech giants as IdPs. Furthermore, its primary focus is on

organizational identity (KYB) rather than individual identity, distinguishing its core use case.

This structure reveals a crucial strategic dynamic: the core battle in the future of digital identity is over the nature of the trust anchor. For the highly regulated world of financial services, the vLEI model's quasi-regulatory trust anchor may be its most compelling competitive advantage. Financial institutions are inherently more comfortable building on a foundation endorsed by global standard-setting bodies and regulators than on one rooted purely in the sovereignty of an individual user or the commercial interests of a large technology company.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Digital Identity Models

4.2 The Rise of State-Sponsored Digital ID: Assessing the Impact of Government-Led Initiatives

A powerful parallel trend shaping the identity landscape is the global move toward government-sponsored digital identity frameworks. Rather than leaving digital identity solely to the private sector, many nations are building foundational infrastructure to provide citizens with a secure and verifiable digital persona.

The most ambitious of these is the European Union's Digital Identity Wallet (EUDI Wallet). Mandated by the eIDAS 2.0 regulation, this initiative requires all 27 EU member states to offer a free, secure digital wallet to their citizens and businesses by 2026. This wallet is designed to link a user's national electronic ID with a host of other verified attributes, such as driving licenses, academic diplomas, and bank account information. Critically, its use for Strong Customer Authentication (SCA) will be mandatory for regulated private sectors, including banking and financial services, fundamentally reshaping the digital onboarding and authentication landscape in Europe.

The United States, in contrast, has a more fragmented approach consistent with its federal structure. There is no national digital ID card, but a growing number of states (13 as of mid-2025) are offering mobile driver's licenses (mDLs) that can be stored in smartphone wallets. Federal bodies like the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) are actively running pilot programs to test the use of these mDLs for high-assurance use cases, including opening financial services accounts. State-level initiatives, such as California's "Access California" project, are also being developed to create a unified gateway for citizens to prove their identity when accessing government services and benefits.

This trend is global, with countries like India (with its Aadhaar system) and Canada (with provincial SSI initiatives in British Columbia) demonstrating the power of government-led ID programs to drive financial inclusion and reduce fraud.

These state-sponsored initiatives should not be viewed as direct competitors to the vLEI model, but rather as potential platforms for co-opetition. The EUDI Wallet, for example, is explicitly designed to be a container for various types of verifiable credentials issued by trusted public and private sources. A vLEI credential (representing a company) or an OOR credential (representing an executive's role at that company) could become essential credentials held

within the EUDI Wallet, used to facilitate secure B2B or B2G transactions. The strategic imperative for GLEIF and its partners is therefore not to compete with these government wallets, but to ensure the vLEI standard is technically and legally compatible with them.

This dynamic points toward a future bifurcation of digital identity into two distinct but interconnected layers:

Foundational/Civil Identity: This layer, increasingly anchored by governments (e.g., EUDI Wallet, mDLs), serves to prove a person's legal existence and core attributes ("I am who I say I am").

Attribute/Role-Based Identity: This layer, populated by credentials from various issuers (e.g., vLEIs from GLEIF, diplomas from universities, employment records from companies), serves to prove what a person or organization is entitled to or authorized to do ("This is what I can do" or "This is who I represent").

The future of a seamless digital economy lies in the secure and interoperable interaction between these two layers, where a foundational government-issued ID can be used to bootstrap and control a wallet containing a multitude of role-based credentials.

4.3 Beyond Blockchain: The Role of AI, Biometrics, and Other Emerging Technologies

While blockchain offers a new architecture for identity, it is just one of several powerful technologies reshaping the verification landscape. In the non-blockchain world, the most significant trend is the rise of sophisticated identity orchestration platforms that leverage Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning, and biometrics to create dynamic, multi-layered risk assessments.

Firms like Alloy, Persona, and ACI Worldwide offer solutions that allow financial institutions to move beyond simple document checks. Their platforms act as a central hub, orchestrating data from hundreds of third-party sources—including public records, utility bills, mobile phone data, and social media profiles—to build a holistic view of a customer's identity. These platforms heavily utilize

AI and behavioral analytics, which can passively analyze thousands of signals in real-time, such as a user's typing speed, mouse movements, device ID, and IP geolocation, to detect anomalies and flag potential fraud.

Biometrics are also becoming a cornerstone of modern verification. Advanced facial recognition, fingerprint scanning, and voice identification offer a combination of high security and user convenience. A critical component of biometric verification is

liveness detection, which uses techniques like 3D depth sensing and micro-movement analysis to ensure that the system is interacting with a live person and not a photo, video, or sophisticated deepfake—a threat that is rapidly growing in prevalence and sophistication.

This demonstrates that the market is not moving toward a single, monolithic "blockchain solution" for identity. Instead, it is embracing multi-layered, risk-based frameworks where blockchain is just one powerful component among many. A financial institution's future identity workflow will not be exclusively on-chain. A more likely scenario is an orchestrated process:

A vLEI might be used to authoritatively verify a corporation's legal existence and good standing (the KYB check).

A biometric liveness check might be used to verify the identity of the specific employee logging in to represent that corporation.

AI-driven behavioral analytics might run passively in the background to monitor the session for any signs of account takeover.

The most successful financial institutions will not place a singular bet on blockchain. They will adopt flexible orchestration platforms that allow them to dynamically combine the best tools for each specific task. This means the vLEI/Chainlink model must be designed to be easily "pluggable" into these broader orchestration layers. Its success will be measured not by its ability to replace all other technologies, but by its ability to become the most trusted and efficient component for the specific task it is designed for: the authoritative verification of organizational identity.

Part V: Strategic Outlook and Recommendations

The confluence of crippling compliance costs, rampant financial crime, and transformative technology has created a clear mandate for change in how organizational identity is managed. The decentralized model proposed by GLEIF and Chainlink offers a compelling vision for a more efficient, secure, and interoperable future. However, translating this vision into widespread reality requires a pragmatic understanding of its adoption trajectory and a concerted, collaborative effort from all major stakeholders.

5.1 Adoption Trajectory: Assessing Viability and Early Use Cases

The vLEI is now transitioning from a theoretical concept to a tangible reality. GLEIF is actively building out the ecosystem by qualifying vLEI Issuers across the globe, including Nord vLEI in Europe and Certizen Technology in Hong Kong, and is launching pilot programs to test real-world applications.

The initial adoption of this technology will not be a "big bang" event that immediately replaces all existing KYC systems. Rather, it will be a targeted, niche-driven process focused on use cases where the pain points of the current system are most acute and the value proposition of a verifiable digital credential is most clear. Analysis of early pilots and strategic discussions points to a clear pattern. The most promising initial use cases are those that are:

Organization-to-Organization (B2B/B2G): Transactions between legal entities often involve significant value and complex due diligence, justifying the investment in a more robust identity framework.

Cross-Border: International transactions are plagued by friction from differing legal and verification standards. A global standard like the vLEI can dramatically streamline these processes.

Highly Regulated: Industries like finance and trade are subject to strict KYC, AML, and CFT requirements. The vLEI, with its regulator-friendly origins, is well-suited to help automate and streamline these compliance burdens.

Part of an Open Ecosystem: Systems that need to onboard new, previously unknown organizations (like a trade finance platform or a new digital marketplace) can benefit significantly by offloading the costly verification process to a trusted QVI.

Early examples of this are already emerging. In Hong Kong, the vLEI is being piloted to streamline the application process for university students from Mainland China, a cross-border, regulated (education), and B2G/B2C interaction. Other identified use cases include securing corporate document signing, automating regulatory filings, and enhancing trust in supply chain networks. The European Banking Authority (EBA) has also given a positive signal, acknowledging the potential for the vLEI to serve as a key technical solution to enhance security and efficiency in line with the goals of the EU's eIDAS 2.0 framework.

While these initial applications are valuable, the ultimate "killer app" for the vLEI and Chainlink model is likely to be the identity layer for the burgeoning tokenized asset economy. As trillions of dollars in real-world assets (RWAs)—such as real estate, private equity, and corporate bonds—are represented as digital tokens on blockchains, the need for a non-repudiable, globally recognized, and regulator-friendly method of identifying the legal entities that are issuing, owning, trading, and custodying these assets becomes absolutely paramount. The vLEI is purpose-built for this future, providing the foundational "who is who" for a trusted on-chain capital market.

5.2 Actionable Frameworks for Key Stakeholders

Navigating this transition requires a strategic and collaborative approach. The following recommendations are offered for the key stakeholders who will shape the future of digital identity in finance.

5.2.1 For Financial Institutions

Recommendation: Adopt a "start small, scale smart" strategy. Resist the temptation to plan a full-scale, multi-year overhaul of legacy KYC systems. Instead, identify a single, high-friction, high-value use case for a pilot project. Prime candidates include the onboarding of international corporate clients, trade finance documentation, or participation in a specific tokenized asset platform. Partner with a modern identity orchestration platform to test how the vLEI/Chainlink model can be integrated as one component within a broader, multi-layered identity verification workflow.

Rationale: This approach directly mitigates the immense risk and cost of a "rip and replace" strategy for mission-critical legacy systems. A contained pilot allows the institution to gain practical experience with the technology, build internal expertise, and demonstrate a clear return on investment on a manageable scale. It positions the organization to expand its use of the technology strategically as the ecosystem and regulatory environment mature, without betting the entire compliance function on an unproven, large-scale transformation.

5.2.2 For Technology Providers (GLEIF & Chainlink)

Recommendation: Prioritize deep technical and strategic interoperability with emerging government-led identity frameworks (especially the EUDI Wallet) and leading private-sector identity orchestration platforms. Shift the marketing and development focus from simply "entity identification" to solving the more complex problem of "programmable corporate authority," highlighting the power of OOR and ECR credentials.

Rationale: The strategic landscape is not a winner-take-all market; it is a complex ecosystem where success is defined by connectivity and utility within a larger whole. Proactively building technical bridges to government wallets and creating simple APIs for private-sector orchestration layers will accelerate adoption far more effectively than attempting to compete with them. Becoming the indispensable, pluggable component for organizational identity and authority within these larger systems is the most direct path to market leadership.

5.2.3 For Regulators

Recommendation: Actively foster innovation by expanding the use of regulatory sandboxes. These sandboxes should provide legal "safe harbor" provisions that allow financial institutions and technology firms to conduct live pilot tests of new digital identity solutions in a controlled environment. Concurrently, accelerate international collaboration through bodies like the FATF, the Financial Stability Board, and the Bank for International Settlements to harmonize standards for digital ID assurance levels and establish clear principles for cross-border recognition and interoperability. Provide explicit guidance on the acceptability of specific high-assurance technologies, like the vLEI, for meeting CDD and KYC obligations.

Rationale: Regulatory uncertainty remains the single most significant inhibitor of adoption. A proactive, collaborative regulatory approach that provides clarity and a safe space for experimentation—as demonstrated by initiatives like the FDIC/FinCEN Digital Identity Tech Sprint —will dramatically accelerate the development and deployment of more secure and efficient compliance tools. This ultimately helps regulators achieve their own core mandates of promoting financial stability and combating illicit finance.

5.3 Conclusion: Forging the Future of Trust in a Tokenized World

The global financial system's current model for identity compliance is fundamentally broken. It is defined by a paradox of escalating costs and diminishing effectiveness, trapping institutions in a cycle of inefficient, manual, and duplicative work that fails to adequately deter sophisticated financial crime while creating immense friction for legitimate customers. The status quo is unsustainable.

A new paradigm, built on the principles of decentralization, cryptographic verifiability, and interoperability, offers a compelling path forward. The model exemplified by the verifiable Legal Entity Identifier (vLEI) and the Chainlink network provides a robust blueprint for this future. It anchors organizational identity in a trusted, regulator-endorsed global standard and provides the privacy-preserving infrastructure needed to make that identity portable and useful across a multi-chain, multi-system world. This approach has the potential to transform compliance from a reactive cost center into a proactive, automated, and efficient utility.

However, the journey from vision to reality is not guaranteed. It requires navigating a labyrinth of fragmented global regulations, overcoming significant technical hurdles related to scalability and legacy system integration, and carefully balancing the promise of transparency with the non-negotiable demand for confidentiality. The ultimate success of this or any new identity framework will not be determined by the elegance of its technology alone. It will be forged through the pragmatic and strategic collaboration of the entire ecosystem: financial institutions willing to pilot new solutions, technology innovators committed to building open and interoperable systems, and forward-thinking regulators dedicated to creating the clarity and confidence required for a new foundation of programmable trust to take hold in the digital economy.